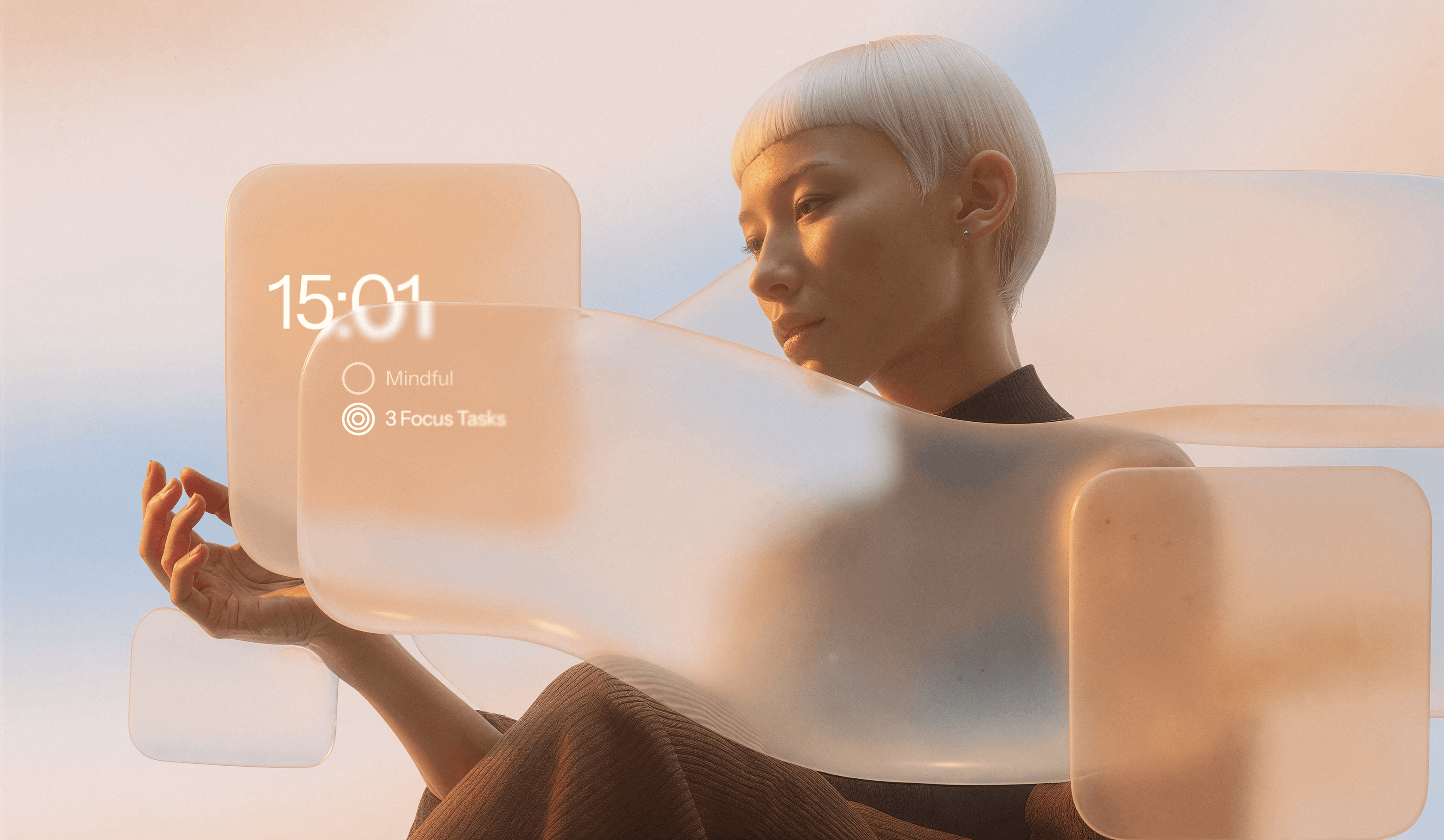

We accept interfaces designed for millions of users instead of the one user who matters: ourselves. But our actual relationship with technology is deeply personal.

Series Introduction

Future Interfaces started with bits of research, some observations and friction points we've been noticing across the industry. It wasn’t meant to become a series, but the more we looked into it, the more it started to form its own shape.

Much of the current conversation around UI design still focuses on screens, layouts, and patterns built for predictable interactions. But that no longer matches how we use technology or how technology is beginning to respond. Interfaces are starting to adapt in quieter, more context-sensitive ways. They shift with routines, adjust to pace and mood, and sometimes act without being asked.

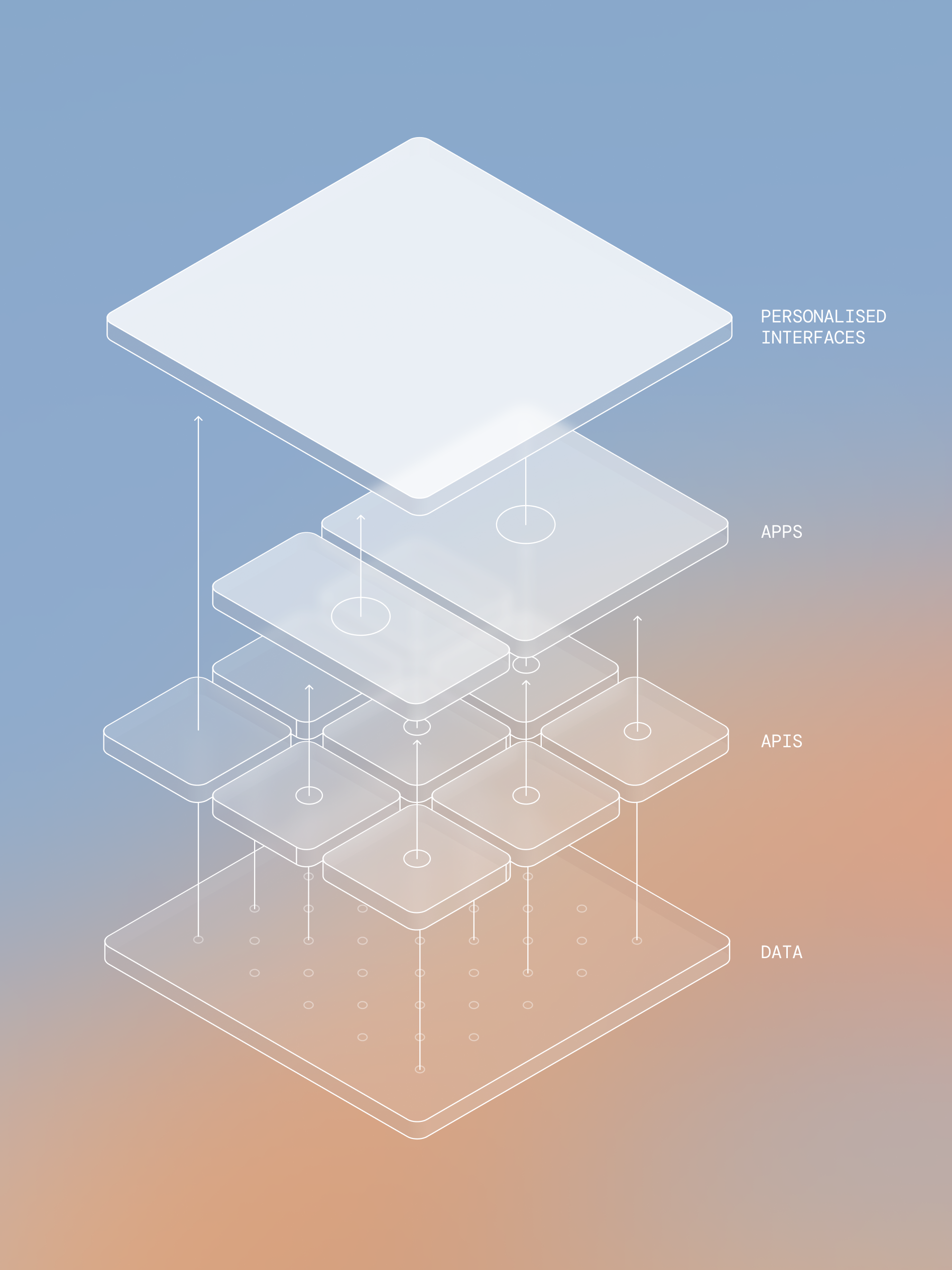

This series gathers early thinking, visual studies, and speculative directions across three layers of interface logic: how it adapts, how it appears, and how it thinks. Together, they offer a view of the interface as something less rigid, more situational and closer to behaviour than display.

From Neural to Digital Plasticity

Your brain rewires itself constantly. Neural pathways strengthen with use, unused connections fade, and entire regions can shift function when needed. This biological plasticity—the ability to adapt structure to meet changing demands—is about to become the defining characteristic of our devices.

Most interfaces are built for everyone, even though each person uses technology in their own way. The way you plan, organise, and make sense of things follows a pattern that’s yours alone. This is about to change in ways that will make the smartphone revolution look like a warm-up act. When devices gain the ability to generate, modify, and deploy code in real-time, the entire concept of "apps" becomes obsolete.

The Plasticity Principle

The capability already exists—AI is already coding apps and prototypes at remarkable speed. Developers are building entire applications using tools like Claude Code, Cursor, and Windsurf, with some creating functional prototypes from single prompts. Windsurf alone attracted enough attention that OpenAI acquired it for $3 billion in May 2025, while developers report "clammy hands and racing hearts" at how powerful these tools have become.

When Software Starts Writing Itself

Claude Code can analyse a codebase, coordinate multi-file changes, run tests, and turn GitHub issues into pull requests, while Cursor handles real-time completion and large-scale updates with impressive precision. Windsurf’s Cascade system provides deep contextual awareness and can run on production codebases and platforms like Lovable.dev bridge design and engineering through visual editing that keeps code visible and alive.

These tools still operate in the traditional model: external services, cloud dependencies, subscription fees. The quiet breakthrough came with Apple’s Foundation Models, launched in June 2025. With just a few lines of Swift, developers can now access on-device models with billions of parameters capable of generating functionality in real time. This is the missing piece: AI already writes code, and iOS now brings intelligence inside the hardware, opening the path toward devices that generate their own software locally without relying on external systems.

The implications extend beyond new apps. Operating systems are becoming adaptive foundations that create, modify, and dissolve functionality on demand—treating software as something alive, responsive, and temporary. Instead of managing a collection of pre-built applications, future OS architectures will orchestrate dynamic software generation—creating exactly what you need, when you need it, then allowing it to evolve or disappear based on usage.

Like the brain, this new architecture works on two levels: conscious direction and unconscious adaptation. You can ask directly—“Create a tracker with these three fields”—and watch it appear, while the system quietly learns, reshaping itself around your habits and blind spots.

The Operating System as Organism

This shift moves us from consuming software to co-creating it with our operating systems. Instead of managing a library of static applications, the OS becomes a living substrate that grows functionality organically around your needs.

Traditional systems act as file managers and application launchers, while adaptive ones evolve into creative partners—understanding context, generating solutions, and maintaining the delicate balance between stability and change. Your device becomes a collaborator in problem-solving, a living environment shaped by your patterns and intentions rather than a toolkit designed by someone else.

Need to track a project with unique parameters? Describe it, and watch the interface appear. Want to link fragments of information in ways no existing app supports? Ask for it. Working on a presentation? The system might generate a temporary research surface that fades once the work is complete, leaving only the distilled insights behind.

The implications reach through every layer of digital experience. Workflows turn fluid as functionality emerges and dissolves on demand, orchestrated by an OS that treats software as a renewable resource instead of a fixed library. Privacy becomes architectural—when functionality is generated locally, data stays within the device. Personalisation deepens endlessly, no longer confined to preset templates or distant design decisions, limited only by what the system can imagine alongside you.

The Collaboration Challenge

This future brings its own complications. If devices can rewrite themselves, how do we keep them secure? If interfaces shift constantly, how do shared ways of working survive? When every system grows into something unique, what happens to teaching, troubleshooting, or passing on knowledge?

The challenges are real, yet manageable. The same local intelligence that allows an interface to adapt can also draw its own boundaries, uphold common standards, and translate between different personal systems and interface languages.

More deeply, it calls for a new design philosophy. The UX principles we rely on today were shaped for fixed structures and predictable user journeys. Tomorrow's design thinking will need to account for interfaces that evolve, learn, and sometimes surprise even their users.

The Intimate Machine

Perhaps the most significant shift is psychological. When your device can reshape itself to match your needs, it becomes less like a tool and more like a partner. This relationship will be more intimate than anything we've experienced with technology.

Your adaptive device will know not just what you do, but how you think. It will recognise your patterns before you do, suggest connections you might miss, and gradually become an extension of your mind in ways that feel both powerful and unsettling.

This intimacy demands new responsibility from both users and creators. We're approaching a moment where devices can mirror how we think, and how we design these systems will determine whether they amplify our unique ways of thinking or diminish them.

Addendum: October 2, 2025

While preparing this article, Nothing announced Nothing OS 4.0 & Essential Apps—a system where users describe what they need and AI generates custom widgets. "Capture receipts from my camera roll and export a finance-ready PDF every Friday." CEO Carl Pei describes a future of "a billion different operating systems for a billion different people."

A major hardware company just took the first real steps in this direction. Interestingly, they're currently focused on cloud-based infrastructure instead of on-device—relying on Android as their base layer, which may suggest their vision is ahead of the technology. But it's incredible to already see someone taking these first steps. The industry is moving, and we're excited to help guide how intelligent devices evolve from here.